A Portrait & Storytelling Project

The American Superhero

The American story is a composite of incredible diversity and real-life superheroes who come from a range of vulnerabilities and backgrounds to express their true selves.

This photo essay began on March 23rd, 2019, at a decommissioned immigration building in Seattle. The work is inspired by New York City-based cartoonist, speaker, and performance artist Vishavjit Singh, aka Sikh Captain America. In the aftermath of the August 2012 massacre at a Milwaukee Sikh gurudwara by a white supremacist, he’s donned the uniform of Captain America to challenge stereotypes, ignorance, and bigotry with humor, compassion, and art.

We present to you an ever-expanding collection of everyday superheroes whose stories of resilience and tenderness exemplify life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Among these portraits are a performance artist-turned-pastor in the immediate aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy; a college student whose mother was just deported; a high school teacher of 20 years battling ALS helping to create cutting-edge technology for paraplegics; eight-year-old identical twins who have each come out as transgender; a 99-year-old who served in the Navy as a nurse during World War II; a survivor of Cambodian genocide who found safe haven in America while his father, a New York Times photojournalist and subject of the acclaimed 1984 film The Killing Fields, was held in a prison camp for four years; the first South Asian American woman to preside over the U.S. House of Representatives; a multiracial baby whose mother, an Eritrean refugee, dreams of genuine equality for him so she doesn’t have to worry about his safety as a young man out on the streets of America.

There is a superhero within us all, regardless of our nation of birth, beliefs, orientation, gender identity, race, abilities, or family makeup. This collection celebrates those differences, highlights our commonalities, and embraces what makes us each uniquely American.

— Nate Gowdy, Vishavjit Singh, Christie Skoorsmith, Gregory L. Evans, Neil H. Buckland, and Co.

Vishavjit Singh, 48

Cartoonist, speaker, performance artist

“Born in Washington, DC, I have felt for most of my life like the ‘other’ … getting bullied as a young boy, surviving a genocidal massacre of the Sikh ethnic minority on the streets of India, and being told to go back home countless times by fellow Americans from Los Angeles to New York.

“After the tragedy of 9/11, I found myself as an American mourning the loss of life while being the target of ignorance, fear, and bigotry. An editorial cartoon featuring a Sikh character in the aftermath of 9/11 captured my predicament. That was the spark for me to start cartooning and to give voice to my story by portraying characters who look like me—with turban and beard. Today I am a storyteller traveling across the nation sharing my vulnerabilities and strengths to find connection with the stories of others.

“America to me is a collage of incredibly diverse stories with twists and plots spanning the globe. There is darkness, there is light, there is tragedy, there is redemption, there is intransigence, there is innovation, there is hate, and there is love. To me, our greatest strength and vulnerability is this amazing collection of tales. To create a space for each one of our stories to be told and heard is our greatest pursuit.”

Pramila Jayapal, 53

US Representative for Washington’s 7th Congressional District

“Defining moments for me have been coming to the United States when I was 16 years old, by myself, as an immigrant, with really nobody around me, and really feeling what that meant—to be in a whole new country with no family; having my child, who was born 1 pound, 14 ounces, at 26.5 weeks and really by all accounts should not be here but they are a beautiful 22-year-old now—that taught me so much about what courage means; starting my organization after 9/11 and fighting against bullying, against hate, for immigrants, and for justice in the world, and turning it into the largest immigrant advocacy organization in the state and one of the largest in the country. And now, getting to be an immigrant in Congress, one of only 14 of 535 members of Congress who is actually an immigrant—the first Indian-American woman. These are moments that I look at and say, ‘Okay, they have given me strength, they have given me courage, and they have given me enormous responsibility.’

“Sometimes people ask me why I don’t just focus on one issue, and why I’m working on so many things, and I respond that I am intersectional. I am not a woman on Monday and an immigrant on Tuesday, a mom on Wednesday and a worker on Thursday. I’m all of those things all of the time. And that’s why we have to understand we are most powerful when we work on all of these issues that make us beautiful human beings.”

M and L, both 8

Transgender twin brothers

M: “I want to be a hot dog seller and I don’t want to have a house. I want to have a minivan as a house.”

L: “I want to sell hot dogs, too. I want to travel around the world selling hot dogs.”

***

L: “I love having a twin as a brother and I like being transgender because it makes me feel special.”

M: “We feel special. And we don’t know a lot of kids that are transgender.”

L: “It was kind of hard at the beginning of the year at school because everybody didn’t know anything about being transgender. So at the beginning of the year they kind of bullied me and my brother. And when we told everybody that we want to be called boys and that we preferred the pronoun ‘he’, people told us that that wasn’t possible and you couldn’t do that. And that didn’t really make us feel very good. And then we told our teacher and she gave us a whole lesson on transgender and gender. Um, and now nobody bullies us. They just say the pronoun ‘he’ to us and stuff.”

Rafi, 72, and Ali Samizay, 11

Grandfather and grandson, born on July 4th

Ali: “I‘m part Afghan and part African American, and I want to be like everybody else—I want to be accepted. When I was really little, I was so used to being constantly loved by family. But when I got into fifth grade, I’m like, ‘What is happening?’ Kids are constantly teasing me. I sometimes sit in my room on my bed and cry about it. I’m not ashamed to admit it—crying is a normal thing. Other times I wonder about why I’m not accepted.”

***

Rafi: “Ali tells me, ‘Papa, you’re old school,’ because I keep a certain distance from technology.”

Ali: “I understand about social media and privacy. But when you can’t use a remote, that’s different….”

Rafi: “I’m very conscious of my privacy. In Afghanistan I was followed and imprisoned for two weeks. Other people never came back, including friends. I was walking to lunch when the car stopped and armed men took me. They had ransacked the house and found boxes of my photographic slides, which they assumed must be politically motivated. So I always have this fear of being wrongly accused.

“I came to Chicago to study architecture under Ludwig Mies van Der Rohe in 1965. When I went downtown and saw these tall buildings that I’d only seen in pictures, that left an imprint on me. And I also didn’t expect to see the black communities. The only black person I had ever seen was Duke Ellington at the stadium in Kabul in 1963. What a thing to hear jazz music in a soccer stadium; the same stadium where, in the times of the Taliban in the late 1990s, they held public executions.”

Annise Parker, 63

CEO & President of Victory Fund

“I’m the former mayor of Houston. I’ve been a lesbian activist for more than 40 years. I was blessed to have a mother and a grandmother who were both college graduates, and the expectation was that I would educate and support myself and that education was a power no one could take away from me.

“My wife and I were married almost 6 years ago on our 23rd anniversary, so that’s nearly 23 years of living in sin and 6 years of having a relationship honored by the state. We have 4 children. Our eldest was 16 when he came to live with us—on the streets because he was gay. That is a sin and a crime, and it gave me a passion for working with homelessness.

“I am old enough to have experienced what life was like before Stonewall, and was 13 when it happened. It was a very different time and place; I was a vulnerable and frightened kid. It was scary and frustrating, but sooner than later I realized we have no other choice but to get involved to try to make change. Everybody needs a hero, and what I understand today is that we can each be our own superhero.

“Every one of us has a gift, even if it’s just the gift of kindness. We can keep our gift inside or we can share it with the world. It doesn’t have to be something that is the bright shiny thing that everybody pays attention to. Mine is being very quietly persistent. I don’t have to be out front, but I don’t want to be the last one in the door. I don’t have to knock the door down, but I will keep knocking. Doesn’t open? I’ll find another one.”

Giselle Lopez, 18

Marketing student working two jobs, future filmmaker

“My dad’s parents are from Germany, and my mother is from an impoverished Mexican village. At 18 she moved to Mexico City to help support her single mother and 10 siblings financially. She fled the country with my sister when her partner threatened to kill her. My parents met in line at IKEA, and my dad would make an hours-long commute across Los Angeles every day to see her. They married one year later.

“My family has struggled and moved a lot since the 2008 recession. Mom’s always worked long, hard hours with no recourse for abusive employers because they’d threaten to report her. On top of that, Dad was diagnosed with degenerative disc disease and Mom is his only caretaker.

“I graduated from high school a year early with a perfect GPA, and Mom dropped me off at college on Sept. 21st, 2018. One week later she got deported; I haven’t seen her since. We were completely in shock because my parents have done everything by the book to file the proper paperwork, going to lawyers since before I was born and spending lots of money. Alone, Dad spiraled into alcohol addiction, and I was almost kicked out of school when I went to go help him move to be with her in Mexico.

“I like to go to Mexican restaurants because it’s the closest I can get to reminding me of my mom and her cooking. It’s the only thing that kind of keeps me sane. I literally have $2 in my bank account and I’m working two jobs to try and survive with no one. Captain America was my favorite superhero when I was little. It’s kind of ironic because he’s super patriotic and … yeah, I can’t really relate to him right now.”

Aris Tewelde-Hunt, 6 months

All-American child

Nahid Tewelde, Aris’ mother, 29: “I’m Eritrean and my family immigrated here with me when I was a baby—first to Dallas and then Seattle. And so, for some reason, seeing the flag and the red, white, and blue growing up was really triggering for me—something that I’ve been trying to break down and understand. The only time I felt slightly comfortable saying that I was American was when Obama was president. And I want my son to understand his identity and not to have such a huge conflict. I want him to be able to be proud to say that he’s American because we have so many different types of Americans and I don’t want him to feel like he has to reject part of his upbringing. I want Aris to be able to look at these photos and in the future say, ‘You know, I’m proud to have been a part of this project.’”

Mary Yu, 62

Washington State Supreme Court Justice

“To be an American means to fully embrace who I am. I’m the daughter of immigrants. At 7 years old, my father left China and grew up on a cargo ship. One day it docked in New York and—along with all the others, primarily Irish immigrants—he just left the ship and never returned. After making his way to Chicago, he fell in love with and married my mother, who’d come from Mexico as a farm worker. She returned to Mexico and entered the United States legally while my father declared himself a refugee, and eventually they were issued the proper documentation.

“After Jay Inslee, governor of Washington state, decided he wanted to appoint me, we walked over to the Supreme Court in The Temple of Justice. It was a bright, sunny day, and in that moment my parents, who’re now deceased, came to mind: I felt a moment of complete gratitude for their unbelievable sacrifice. Factory workers on Chicago’s south side, they dared to dream about giving their daughter the opportunity to be who or whatever she might be. Today I’ve been on the Washington State Supreme Court for five years, and I just happen to be the first Asian, the first Latina, and the first lesbian to serve on the bench.

“It really matters that a brown kid might look at me and say, ‘I could do that.’ I would like every kid in the state of Washington, no matter where you’re from, no matter who you are, no matter your identity, to earnestly believe that they could be me—that if I can do this, you can do this. The idea of inviting people to be visible and to be full participants in our systems of justice, to me, is what it’s all about. We make better decisions when we reflect the communities we serve.”

Aleksa Manila, 44

Social worker, activist, drag queen

“My journey coming to America began when I joined my family here in Seattle from the Philippines in 1995. Ten years in, I became a US citizen. At the time, the idea of being gay was being challenged and there was that talk and risk of being deported because of it, so I wanted to avoid that. I also held the title of Ms. Gay Seattle, so I wanted to become a U.S. citizen so I could do my part in motivating others to vote.

“Drag is my superpower because it allows people to be inspired, to be encouraged, to dig deep, and to see the beauty that exists inside and out. I’m thankful to all my drag queen and drag king ancestors—particularly African American, Latinx, Puerto Rican, and Asian—who fought hard at Stonewall in New York City 50 years ago so that I could express myself in this powerful way.

“To be American is to be able to live freely, have autonomy over our bodies, and to be proud of whoever we are, wherever we come from, whatever belief systems and family values we adhere to, as long as they come with love, respect of ourselves, of our individuality, and of others. And not just our family members, but truly any person we see, whether that means a brown person like me or an immigrant like me. We can all coexist with love, with pride, and knowing that—at the end of the day when we close our eyes—we’re all the same America.”

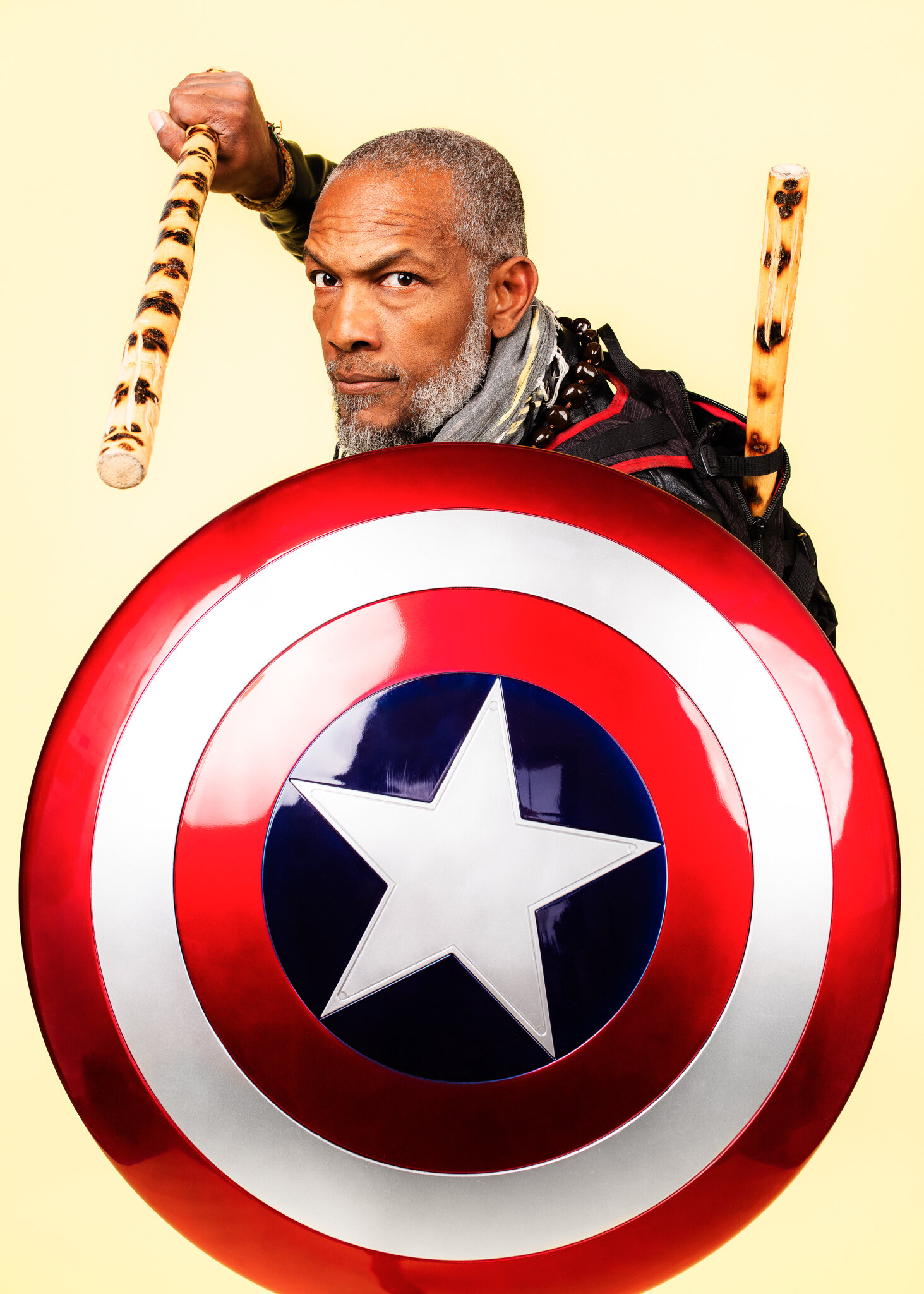

Stephen Sinclair, 67

Minister of faiths, healer of souls, joy maker

“On September 11th, 2001, while walking my dogs over to the Hudson River in the Greenwich Village where I lived, I heard the sound of two low-flying planes. I then witnessed everything that happened, standing there with my neighbors in utter, total disbelief. At one point, I thought I saw birds or pieces of debris falling from the burning towers. And it wasn’t until I looked more closely that I realized it was people jumping. And in that moment—even though I loved acting and singing as a performer—I knew it was time to answer the call from the god of my understanding. Soon thereafter, I went to seminary in Chicago and became a chaplain and a parish minister and many other things besides. So, by bearing witness to that calamity and the tragic consequences it had in every aspect of life, I hope that in my small way I have been a healing balm, that I have given people hope.”

***

“I’ve never really, truly felt American. I grew up with a German-born mother who was an immigrant to America after World War II. Because of her influence I identified so much with being European, but I really felt like a citizen of the entire world, the result of my spirituality, a combination of Hinduism, Judaism, and Christianity. I’ve always tried to fit in and to be an American, but I know that is just a construct created by the power of the nation-state. In truth we are all one. I would love for this country to embrace that.”

Gay Lloyd Pinder, 73

Speech language pathologist

“I grew up in Virginia in the 1950s. Pa was an episcopal minister and he had a church, a white church, and his best friend in town was the black episcopal minister, of the black church. They were working to bring the two congregations together. One night the Mitchells came over for dinner—happened often. The next day my best friend Betty came up to me on the playground and she said, ‘I heard something about you. Did you have a black family come to your house last night?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, it was the Mitchells. They’re wonderful.’ And she said, ‘Well, I was hoping that wasn’t true. I can’t ever talk or play with you again.’ Three weeks later, at probably 2 a.m. I saw a cross burning out on the yard. Not knowing anything about the whole racial situation except for Betty, I just thought, ‘Odd,’ and didn’t wake anybody. In the morning I told Pa and he said ‘yup’ and explained, and I just sort of internalized and went with it because my family never looked back. They just kept right on going.”

“I began to lose my hearing in my late 30s, and so I’m a part of the deaf community that’s identified as late deafened. I moved to Seattle from Maine, where I learned ASL as fast as I could with Jean, my partner. I met up with many deaf people and they became my teachers. Then I met up with many deaf-blind people and they became my heroes. I’m still in many ways a baby deaf person and they’re still teaching me despite the fact that the first kids I worked with are now 60 years old.”

Tito Dith, 49

Physical therapist, small business owner, family man

“I left Cambodia at age five. I remember hearing helicopter noises and the smell of diesel engines and being separated from my dad who was covering the story of the civil war in Cambodia. And I remember coming to America, not knowing the language, here with my mom and my three siblings, and it was a struggle. But my mom kept us all together and she always told us to keep thinking about my dad … that some day he would join us. I remember her telling us that on every birthday—‘You know, I wish that your dad was here with us.’ And then that moment when we heard the news my dad had made it across the border into Thailand. Receiving that phone call, we were just so elated—jumping, screaming, and then being reunited at the airport, that was an amazing part of my life.

“I believe my dad had superpowers in the will to survive — that drive. What was behind that was the fact that he wanted to tell the world about the genocide in Cambodia, and he needed to survive in order to tell that story.”

Editor’s note: Tito’s father Dith Pran played a significant role in bringing the crimes of Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge regime to the world’s attention as a photographer for The New York Times, enduring four years as a slave laborer. He was the subject of the 1984 Academy Award-winning movie, The Killing Fields.

Cassandra Jackson, 37

Customer avenger, traveler

“I was in Korea once visiting my brother who was living there and there were two lines at customs: one for the Koreans and another for the non-Koreans, and everybody in the Korean line looked Korean. In America, you look at our lines at customs and everybody’s American but also looks different. And I love that about America, that I have Indian friends, Hispanic friends, white friends, black friends. I’m Christian; I have friends who are not Christian. Being American is having the freedom to define what that is for you.

“A superhero in real life to me is someone who is vulnerable and honest and open to change. I always think about Malcolm X. He had the frame of mind to be able to change his mind and his thoughts—things that he was vocal about for years. He learned and he changed and he pivoted and he was able to express that even though people were like, ‘You know you changed your mind about what we were following you about before?’ And he’s like, ‘No — I’ve learned and I’ve grown.’ That to me makes an American hero.”

Jeremy Best, 51

High school music teacher, musician, indefatigable somnambulist

“I believe diversity in this country must be cherished and emphasized, especially during the time of this president.

“My superpower has become pioneering technology so that people like me can make music in the future. Music technology for quadriplegic people, man! I was in a band pre-diagnosis, but more importantly I have been working with Microsoft on the eye gaze music project and recently have been involved with the excellent encephalophone adventure. Both are new and exciting technologies that offer real hope for the future. I am also working with a VR man exploring ways we could use VR as an assistive technology.”

Ora Monton, 8

Student

“Being American means trusting and helping and knowing that things are going to happen the right way. My superpowers are being inventive and creative and caring. And being able to lift things that are heavier than me. My vulnerability is my shyness.”

Nima Forghani, 36

Systems engineer, filmmaker, export of Iran

“I remember going to the bomb bunkers in kindergarten. During nightly raids, dogfighting fighter jets bombed everything they saw. Schools and hospitals would get leveled. There was no Geneva Convention. Iran lost about 1 million people in the Iran-Iraq War, and another 6 million were disabled. I once witnessed a public execution when my mother and I were walking through a bazaar shopping. I grew up in constant fear of war and my own government.

“A doctor and intellectual, my dad was harassed by the Islamist regime. Our own country didn’t want us. One thing he always said, and I will never forget these words: ‘No matter what, the last place that will fall will be America, so we want to be there.’ In 1999 we were granted political asylum in Canada and then, finally, we got our American green card from the U.S. embassy in Canada. A process that took 20 years as Iranian nationals took us six months as Canadians.

“Despite all the hate that’s happening with the political nature and the division that’s currently here, I want us to take ownership of that vision of what it is to be American. We have a great opportunity—with the help of all the immigrants and people who came here for a reason—to put people on our shoulders and take them further. Being a patriot isn’t necessarily flying a flag or wearing red, white, and blue, but actually holding the hand of somebody who’s in need. There are great Americans who are everyday heroes and we don’t hear about them.”

Mary Elisabeth Hancock, 99

City gal, World War II nurse, retired rancher

“My mother was given up to die. I’ve always felt she might have had cancer in the cervix, but in those days they didn’t have all the tests like they do now. She was about 45 or so—very young and very sick, and that’s when I decided I was going to be a nurse. Anyway, they operated on her and gave her radium treatment, which burned her … she was so burnt. But apparently it got to it because she lived to be 89. And, you know, this is the honest truth and I haven’t told this too much to anybody, but she started to get better the week after my brother and I were baptized on Easter Sunday. The doctors were shocked. I always said the Lord helped us.

“When I graduated from nursing school in 1942 I enrolled to become a Navy nurse and was stationed at Brooklyn Naval Hospital for six months to get all your shots and get oriented. Then I was transferred to one of the outlying fields in Pensacola, Florida. For quite a few months, before the WAVES [Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service] came in, it was just me and two other women who were nurses. We cared for thousands of men—cadets, enlisted men, and officers.

“I was there a year and a half before I fell in love and then got married. He was a Marine fighter pilot who taught the cadets to fly. There were a lot of crashes. And I used to go out with a doc to these crashes, which were bad. I don’t remember any of them surviving. Learning to fly was dangerous and it was a very sad time.”

Editor’s note: Representing the US Navy Nurse Corps, Mary shook President Franklin Delano Roosevelt hand in 1942.

The Vasilez Family:

Jennifer, 34; Josh, 36; Maya, 3

Syayayəʔ (Lushootseed for “family”)

Jennifer: “Even though I can claim identity with multiple ethnic groups and am enrolled in the Puyallup Tribe, I didn’t grow up in a traditional way. When Kennedy—an Irish-Catholic—was elected president in 1960, it meant a lot to other ethnic communities. My grandparents bought into and valued the idea that if you just assimilated you could be successful. As a result, I don’t speak Spanish and my native indigenous language fluently. But it’s not just me who’s had to re-indigenize myself, it’s much of Indian country. There’s the history of boarding schools and other things where native spiritual practices and languages were made illegal or people were punished for participating in them.

“I’ve been blessed to be a teacher and now I’m the principal of a tribal school, where we’re incorporating native knowledge and practices into all subject areas—because our ancestors were social scientists and everything we have today. Both opportunities have helped me reconnect with my community, and I’m learning as much as possible so I can pass those teachings on to my daughter.”

***

“Earlier incarnations of Captain America had a jingoistic element. He was often pitted against stereotypical representations of villains from other countries. I think earlier generations defined patriotism that way, but that doesn’t have to be how our generation defines it. To me, being patriotic means advocating for a country that will do right and that represents justice for all—not justice for some. Our collective voices and experiences empower us as a nation.”

Jin-Ah Kim, 29

Former city council candidate, current wrangler at a tech company

“I was a photojournalist, or I thought I was going to be. I tried to live by that whole, you know, Joseph Pulitzer quote: ‘We will illuminate dark places and, with a deep sense of responsibility, interpret these troubled times.’ And then opioid addiction took me away from that. I unintentionally got into politics through Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal. I was the first female in America to ever run for office publicly open in recovery from an opioid addiction. There are few places in the world where you can go from homeless to running for office in less than three years. That’s remarkable. And that’s what I think is very American.”

“During my campaign, my political consultants told me to change my name. Their top three choices were Emily, Victoria, or Olivia. That was interesting because my name is Jin-Ah—it literally means ‘true self’ in ancient Korean. Well, it’s time to live up to it; 29 years is enough. I’m polyamorous. My philosophy is that to expect one person to fulfill all of my spiritual, physical, and emotional needs is toxic. This does not mean I’m running from commitment—quite the opposite. It means multiple committed relationships and, hah, Google calendars. Love is fluid and should evolve organically.

“I’m also genderfluid. I’m still very binary presenting so I’m still comfortable with she/her pronouns, but this may change. Every year during Pride month, I used to think to myself, ‘Will this be the year I come out?’ And I’ve always struggled; no more. When I tried to sign up for benefits at work and I couldn’t identify as non-binary, I realized that this is the kind of thing that makes it important to come out. Visibility is super important!”

Alexander J. Sherwood, 33

Veteran, entrepreneur, pre-med student

“I grew up in a really small farming town in upstate New York, called Windsor, a ‘more cows than people’ kind of place. We had a blinking yellow light that flashed both ways at the main intersection in town, but I think that was just so people driving past on the highway would know we had electricity. After I graduated high school I did a little bit of college and game development, then decided to join the Army. I started in the 82nd Airborne and then moved on to earn my Green Beret, including a combat deployment to Afghanistan and some time in the South Pacific. I injured my back on a parachute jump and my body made the decision for me to slow down and pursue other things, including a molecular biosciences degree, with the hope of eventually attending med school and just continuing to care for and protect my communities.

“I think it’s something that people have kind of lost sight of, but, to me, being American means that you are part of something bigger than yourself. Sure, the flag represents our history—everything that people came from and brought with them from elsewhere in the world, everyone who is now here and part of this country—but I’ve had friends come home under that flag, and for me that’s a powerful reminder of just how much a person can sacrifice and give of themselves to this. Whether you came from somewhere else or not, there’s this ideal that you can do or be more. I think being an American is … you’re pursuing that. You’re trying to have a better life and improve things for others. Being American is recognizing that we’re at our best when we stand together rather than divided.”

Sawyer Benbow, 20

Food service worker, aspiring college student

“My depression and ADHD can make it difficult to do pretty normal things. And people’s perceptions versus the reality makes it harder … the contrast is so stark. People are still out there saying ADHD doesn’t exist, and even when they’re aware it makes it harder to focus on things, they don’t comprehend that it affects other emotions and can make it a struggle to begin tasks … even as basic as getting out of bed.

“I’d like to go to college, but I have doubts it’s an attainable goal. With my mental illnesses—even if it were free—I don’t know that I could balance college and a job very well. Even if I work full-time, can I make enough to support myself? College exists essentially as a class barrier in this country. I feel stuck. It shouldn’t be this way. College shouldn’t bankrupt people trying to better themselves.

“The American dream is more or less a lie. Even F. Scott Fitzgerald alluded to how antiquated and materialistic an idea it is. Having things and living a life are different—success should not be measured by what you own but by who you are and, to an extent, by your experiences.”

***

“Being a superhero means working toward the greater good no matter the personal cost. Captain America is meant to represent the idealized version of what America can be. His moral compass is what we should be and what we often aren’t. Captain America—standing up for what’s right, even when it’s difficult and in contention with what the government is doing—is so inspiring to me.”

Roman Leal, 32

Working creative, Renaissance man

“The white kids didn’t like me because I was Mexican. And the Mexican kids didn’t like me because I wasn’t Mexican enough. To them I was the worst kind of Mexican—one who didn’t know how to speak Spanish. The reason I didn’t speak Spanish was because my father knew how hard it was being an immigrant from Mexico with an accent whose first language was Spanish, so he tried to protect us by removing any kind of Mexican culture or heritage from our upbringing. It wasn’t until my teenage years, when I’d already moved out of the house, that I overheard my father listening to Spanish cumbias. I had never ever heard any kind of ethnic music being played in the house—it was always rock and rock. He himself had even whitewashed who he was, all in order to give us a better life in America.

“American superheroes like Superman and Captain America—have historically been kind of the boy in blue, schoolboy kind of image, which is great in its own right. But I also feel, at the same time, the ‘traditional’ American superhero isn’t a real superhero, if that makes sense. It just feels like a figment of someone’s imagination on how everyone should act. And then there’s never any real vulnerability or sincerity to the American superhero. It feels just … ‘Bullets can bounce off me, I’m faster than this, that, or the other,’ you know?”

Maly Oudommahavanh, 37

Special ed teacher’s aide, unfluencer, taste destroyer

“I am Asian American, but even in the Asian American diaspora, there is such a huge diversity. My family’s from Laos and were refugees. I was born and lived five years in a refugee camp. The Laotian-American refugee experience is quite similar to that of Cambodian Americans and Vietnamese Americans. When you look at their stories and the traumatic things that happened to bring them to our country, there’s a lot of similarity with superheroes who, much of the time, are born out of really adverse circumstances … your family members dying or you being put in a foreign environment—and not by your choice—and then making the best out of it. The difference between a superhero and a supervillain is: What choice do you make? Are you going to stand up for yourself and for others and try to make things better? Or are you just going to respond to tragedy by veering towards the worst of human nature? And I just really think, oftentimes with refugees, it’s more of the superhero side than not.

“What does it mean to be American? Honestly, it means a lot of privilege. Even as my identity is ‘hyphenate-American,’ I still realize that that ‘American’ at the end is super powerful. My passport alone means I can travel to a lot of places. I might still get treated differently because of my status as a woman or as a person of Asian descent, but we as Americans still wield a lot of power and we need to do good with it.”

Korvus Blackbird, 50

Maker of art, music, graphic novels, films, songs

“My superpower in real life is pointing out other people’s superpowers. I’m a teacher so I teach little people, so you have to empower them and inspire them to be their excellence.

“My vulnerability is my heartbeat. Yeah, my heart would be the most vulnerable part of me, ‘cause it’s big and it’s open. So, you need a shield sometimes, right?”

Many more stories on the way!

As seen in …

And shared by …

Congressional Progressive Caucus, Emily’s List, Jewish Voice for Peace, KCTS 9, Pillars Fund, Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-MN), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), Seattle Arts & Lectures, The People for Bernie Sanders, Wing Luke Museum

The Team

Nate Gowdy is a Seattle photographer known for projects centering LGBTQIA+ community, presidential politics and protest, and American identity. His photojournalism has been featured internationally, including on the cover of TIME magazine (Bernie Sanders, June 6, 2016). In March 2019, he maxed out his credit cards to purchase a wide assortment of Captain America paraphernalia for this series, which debuted on BuzzFeed News on July 4, 2019. The Smithsonian soon reached out, interested in acquiring prints once the project was completed. Due to the pandemic and a spin-off commission for Seattle Public Schools in 2020, the project was put on pause. It will resume in 2024 or 2025.

Vishavjit Singh is a New York City-based cartoonist, speaker, performance artist, and creator of www.Sikhtoons.com. He got his spark for cartooning post-9/11 when Americans with turbaned and bearded countenance became targets of hate/bias crimes. For the past few years, he has traveled across the U.S. with his Captain America persona armed with turban, beard, and humor to tackle fear, anxiety, bigotry, and intolerance. He hosts talks and keynotes on diversity, inclusion, vulnerability, and storytelling in schools, universities, and companies including Google, Apple, and NASA. This project is an extension of his mission to start conversations, build bridges, and encourage everyone to step out of their comfort zones to create change, to be the change, and to inspire each other to be better versions of our selves. His work has been featured in The New York Times, NPR, BBC, The Atlantic, Huffington Post, The Guardian, and Time Magazine. An award-winning short film about his life, American Sikh, is currently on the festival circuit.

Christie Skoorsmith is a Seattle native passionate about equity issues, peace, and justice. She has a master’s degree and has lived and worked in various countries teaching in the field of community development. Her focus has been working with communities recovering from natural and political disasters, and currently she works with children with special needs. She has a passion for Gandhian non-violence and has been published in The Global Peace Journal, Geez Magazine, Herald Magazine, and is featured in the book “Mahatma Gandhi: At the Close of the Twentieth Century.” She and her husband are raising three children and have been active in the transgender community since their eight-year-old twins came out as transgender. The idea for this project came to her after attending a lecture by Singh.

Gregory L. Evans has never been a patriot. From a young age, he felt the word had a very negative connotation and has tried to shield himself from supporting the variety of ‘patriots’ who create division in this country. His process with this project has made him feel that we need to reclaim what it means to have passion for the home we were given or the one we’ve chosen. His story as an artist and producer is long and winding. However, one constant principle he’s maintained throughout his life is that he needs to love what he’s doing and to always strive to do what he loves. He continues to press himself to tell human stories that connect us all and create compassion. All intersections of media should be employed to affect this task, whether it is commercial film, narrative work, still photography, or writing. When we work to connect people through the path of the heart, we find relationships in business and society that empower growth for all parties.

Stephen P. Smith is a multifaceted creator and communicator. Stephen grew up in Detroit surrounded by different cultures and socioeconomic conditions. This gave him a deep appreciation and empathy for people from all walks of life. He sees strength in both commonality and difference, and advocates the need for equality to the benefit of all. He is grateful to be able to contribute to The American Superhero Project, as he believes that compassion through understanding is key to building a more peaceful world.

Credits

Photographer & Project Lead: Nate Gowdy

Creative Director: Vishavjit Singh

Project Producer: Christie Skoorsmith

Creative Producer: Gregory L. Evans

Interviews: Vishavjit Singh, Christie Skoorsmith, Nate Gowdy, Gregory L. Evans

Editors: Nate Gowdy, Vishavjit Singh

Lighting Designers: Gregory L. Evans, Neil H. Buckland, Nate Gowdy

Production Assistants: Roman Leal, Neil H. Buckland, Andi Buescher, John Boal, Brien Aho

Retouchers: Nate Gowdy, Stephen P. Smith, Neil H. Buckland

Videographers: Gregory L. Evans, Neil H. Buckland, Brian Racherbaeumer

MUAs: Lisa van Dam-Bates, Noura Rabi, Oliver Villavuerte

Wardrobe: Tiffany Russell, Kourtney Gray, Christie Skoorsmith

BTS: Roman Leal, David Calder, Jon Shields, Brien Aho, Ben Lucas

Awesome intern: Chloe Velasquez

Exhibition printing / framing / hanging: Nate Gowdy, Gregory L. Evans, Neil H. Buckland, Roman Leal